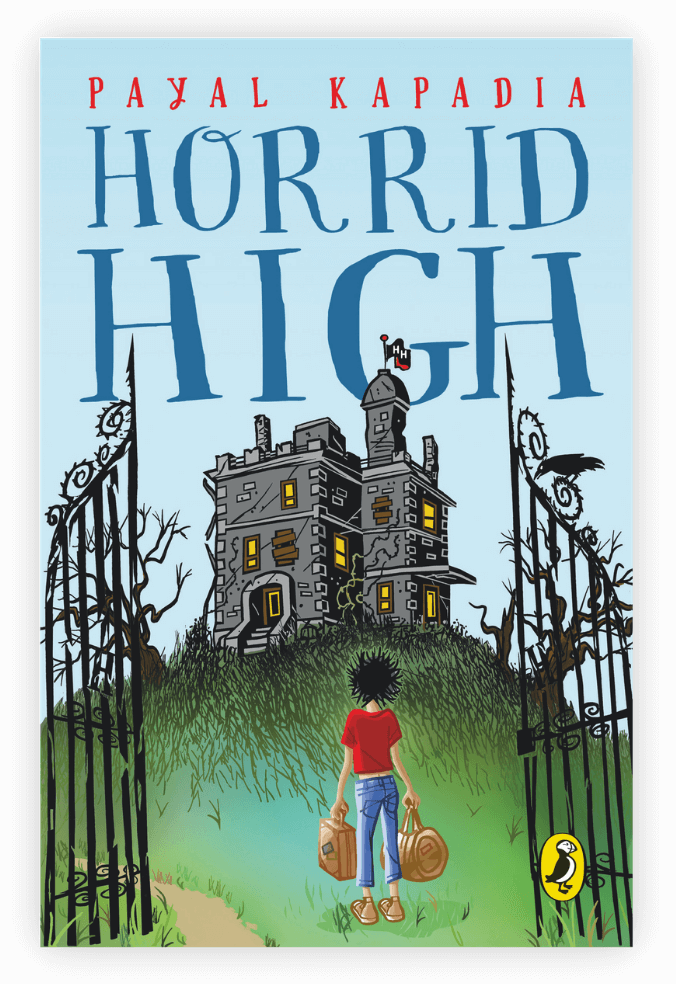

Sneak Peek: Horrid HighCHAPTER 1 If twelve-year-old Ferg Gottin had been bought from a store, his parents would have returned him and demanded a refund. Instead, Mr and Mrs Gottin sent their son to Horrid High and took off for a vacation in the Bahamas. Mrs Gottin hadn’t stepped out of her

CHAPTER 1

If twelve-year-old Ferg Gottin had been bought from a store, his parents would have returned him and demanded a refund. Instead, Mr and Mrs Gottin sent their son to Horrid High and took off for a vacation in the Bahamas.

Mrs Gottin hadn’t stepped out of her air-conditioned room because she was certain that the heat would curl up her hair. Mr Gottin hadn’t stepped into his room because he was certain that sweating it out on the patio would make him thinner. But they were happy—as it is expected that any parent on a holiday without children would be.

Mrs Gottin was reading the Daily Post online: Happy High is actually Horrid High: Tammy Telltale tells all. She stiffened. ‘Darling!’ she called out, a tremor in her voice. ‘D’you think they’ll send him back to us, now that Horrid High is no longer horrid?’

Mrs Gottin felt her hair curl at the thought and she cursed the tropics. Mr Gottin felt his holiday mood curdle and he cursed his wife.

Halfway across the world, another head was bent over the same headlines. This was an exceptionally ugly head, an extraordinarily hideous head, an eminently objectionable head. This head was infested with horrid ideas. They swam around like germs; they whispered horrid things; they seethed to be let loose like snakes in a pit.

The hair on this head was practically fried to a crisp by all the horrid activity underneath. There were large welts of angry skin where the hair had fallen clean off. What hair remained was frizzled and grizzled, like it had been left on a barbecue and forgotten. If you were to run a hand through that hair—and no one except its owner had ever dared do that—you would find that it sizzled.

On the left of this eminently objectionable head, square on its owner’s right shoulder, sat a bamboo lemur.

‘It can’t be,’ the head muttered, and the shoulders dropped so abruptly, the lemur jumped. ‘It can’t BE!’ And now the owner of the head crumpled the newspaper into a large ball and lobbed it across the room, knocking the lemur clean off.

‘Stupid monkey!’ he snarled, even though the stupidity was entirely his to mistake a lemur for a monkey. The lemur skittered away, which was a sensible thing to do because it was the last of its kind left on earth.

‘What about her?’ said the faint voice on the other end. ‘She’ll only be in the way!’

The hairless patches on the back of that head got redder. ‘Leave her to me!’

The head made one more call. ‘Stir up some trouble in the Amazon, cut down some forest, choke up a river or two but enough about how Happy High is actually Horrid High! Give the papers a new story, will you?’

***

Somewhere between the Gottins and the lemur owner, a better-looking head was bent over the same newspaper in a school that had once been horrid. The hair on this head was a gleaming silver. This head was brimful of the sort of rock-solid ideas that save the planet and make children everywhere feel loved.

The owner of this head was also disturbed by the headlines because she knew that there were more ways in the world to destroy something than to save it. Over twenty years ago, she had left this school to start the Grit Movement. It was a worldwide movement now, fighting politicians and business barons hell-bent on plundering the planet for their own gains, and saving animals from the brink of extinction. Last year, she’d returned to find that the happy school she’d left behind was on the brink of extinction too. It was a horrid school now, possibly the world’s most horrid school.

Granny Grit’s face brightened as she remembered how the children and she had pitted their wits against Principal Perverse. How they’d busted the Grand Party he’d thrown for a thousand horrid teachers before he could announce his hideous Grand Plan. Even though they had no idea what the Grand Plan was or where it had vanished, Horrid High was in safe hands now. Why waste newspaper space on it? It was the rest of the world Granny Grit was worried about.

‘Oh dear, thousands of refugees have fled Burma with nowhere to go,’ said Granny Grit, narrowing her chocolate brown eyes. ‘And this makes front page news?’

The children of Horrid High were huddled over the Daily Post. They had been cut off from the world earlier, but Granny Grit always began her classes with news time. They read the papers together, they circled the stories that made them think and they discussed why some of the smallest stories were often the most important. Immy read the story out loud from the newspaper, even though all the children knew it inside out. They had, after all, lived it.

‘An unruly celebration attended by 1000 horrid teachers turned into a police crackdown after ive clever children at Happy High shot a video and took photographs as proof that their school was far from happy.

‘“Happy High is really Horrid High!” says Tammy Telltale, a student and author of the bestselling The Tales of Horrid High. “It is the world’s most horrid school!”

‘In a shocking revelation, Miss Telltale told this paper that her school masqueraded as a happy orphanage in order to receive a generous government grant. “Principal Perverse was a horrid man!” says Miss Telltale. “He dragged me to the Tower of Torture once for no fault of mine!” ’

Immy couldn’t help but stop to mutter under her breath, in a perfect impression of Tammy’s nasal voice, ‘For no fault of mine!’ That certainly wasn’t how she remembered it! Tammy had been threatening to tattle on them. But instead, she’d ended up in the dark, windowless tower where Principal Perverse liked to punish his students. It served her right, it did!

‘Go on, Immy!’ said the class, giggling because the school’s most talented mimic had muttered loud enough for everyone to hear. Immy pulled a face, drew a long breath and resumed reading.

‘It now appears that this horrid school was a training ground for horrid teachers everywhere. The principal and his teachers are in jail now, but no one at school, not even Miss Telltale, will divulge the names of those clever children. Nor does anyone seem to know what a thousand horrid teachers were celebrating that day. It probably doesn’t matter. It is the children of Horrid High who should be celebrating, now that their school is horrid no more.’

The kids drummed their desks with their hands and stomped their feet. In Granny Grit’s classroom, it was perfectly all right to express joy—even if they were a little too loud about it! When the jubilation had subsided, Granny Grit spoke again.

‘The Grand Party has come and gone,’ she said, brushing away a stray white lock of hair. ‘Can you find other stories on the back pages that should have been out front today?’

This was no ordinary classroom and Granny’s style of teaching took some getting used to. There were a few orphans here but mostly, the children were runaways and rejects for whom the school was home. Like Phil Fingersmith, legendary lock-picker whose parents had moved to Somalia without leaving a forwarding address. And Immy Tate, mimic beyond compare, who escaped the circus after her folks abandoned her. Like Fermina Filch, pickpocket par excellence, whose parents had so many children that the novelty had worn off. And Ferg Gottin, with a remarkable memory for the tiniest of details, who ended up at Horrid High so that his mom and dad could forget their tiny detail: him.

Most of the children had ended up at Horrid High because this was a school where you could dump your kids and forget about them. Now, orphans, runaways and rejects are scarcely Most Wanted—unless they’ve committed a crime. But Granny Grit made it a point to make the children feel Most Wanted— to ask how they were, to mark their birthdays, to note what books they enjoyed, and yes, even to seek their opinions on the day’s news.

‘Tammy looks good in this photo,’ said Fermina grudgingly.

Then she asked the question that was on everyone’s mind. ‘Will she be back at school?’

There was a pause as everyone who had known Tammy secretly prayed that she wouldn’t. You see, Tammy Telltale was an incurable snitch and an intolerable snoop. Back when Horrid High had been horrid, she had made life miserable for the other children by swooping down on secrets and eavesdropping on conversations that she had no business listening to. Tammy couldn’t resist a good story, especially if telling that story landed someone in trouble. A horrid school full of horrid teachers set right by five children—what a scoop!

Granny Grit grimaced as she thought of Mrs Telltale, who called her every two weeks. ‘We’re at a bookstore in the mountains now, Grandma Grit, and the entire village has trekked up to hear my Tammy read!’ she said in a voice that set Granny’s teeth on edge, and not only because Mrs Telltale insisted on calling her Grandma! ‘My Tammy’s been practically mobbed by fans and the queue for her readings stretches all the way down two streets!’

Both mother and daughter were having too much fun being famous. Granny Grit was certain that school was a distant thought for them. ‘I don’t think she’ll be back any time soon,’ she said, marking that it had been thirteen whole days since Mrs Telltale’s last annoying call. Thirteen blissful days.

Calls! Granny glanced at her watch. They were only halfway through an exciting lesson, but now she would have to tear herself away from the classroom and attend to calls. She sighed. Being principal wasn’t even half as much fun as teaching.

‘There’s an oil spill in Alaska on page twelve that deserves to be on the front page,’ said Phil wryly. ‘Another leaky ship that forgot to clean up after itself!’

‘You’ll have to wait your turn,’ said an impish girl on the middle bench, making everyone laugh because of the imperious way in which she said it. ‘There’s a fantastic library about to be demolished because no one will cough up the money to preserve it! Page fourteen!’

‘And what about the last page, just ahead of the sports section?’ said Ferg. ‘Children dying of starvation when there’s enough food to go around!’

The children broke into a heated discussion until a tall boy at the back raised his hand. ‘Let’s do this in an orderly way, boys and girls,’ he said. ‘Yes, Immy, what do you have to say?’

Granny heaved a sigh of relief. Her class could manage without her, at least for a half hour. ‘Could I be excused?’ she asked. ‘It’ll be time for lunch soon, and we have a new cook. Highly recommended, too, by the way!’

The class promised not to be noisy—OK, not too noisy—and Granny Grit hurried out, smiling. Horrid High was certainly a happier place with Tammy away, with Principal Perverse in jail and with every last horrid teacher rounded up by the long arm of the law.

Every last horrid teacher. That thought slowed Granny Grit down. Could Horrid High put its horrid past behind it at last? Just then, a loud clatter of dishes from the kitchen made her start. The new cook! Food had been a nasty business for the old cook. Chef Gretta Gross had delighted in making the sort of food that no one could eat. Merely the memory of her Maggoty Pizza and Fermented Fish Soup made Granny’s hair stand on end, and she decided to go downstairs to the dining room. A small detour to see what Chef Gretta’s replacement was up to couldn’t hurt.

She walked a little faster past the Great Hall on the ground floor. That was where Principal Perverse’s whip lay, in a glass case, like the ridiculous red velvet chair he had sat on while hatching his wicked plot to spread horridness everywhere. The Throne. The whip and the chair always brought unpleasant thoughts like flies to a feast. It had been far too tempting to burn them, just as every copy of the Book of Rules had been burnt. Or to bury them or cart them to the farthest garbage dump on the planet, where no one would ever see them again. There! Horrid thoughts were taking hold, even though she’d looked away, but then the aroma of vanilla got into her nostrils.

Ah! It was the smell of freshly baked cake, of birthday parties and warm, loving families. It was as if the new cook had sent the aroma wafting out of the kitchen by way of introduction. And Granny Grit’s mind switched from Chef Gretta to the lunch menu like it was the easiest thing in the world.

The new cook had his back to her. He was leaning over a large pot of something that smelt delicious and bubbled wickedly. He turned quickly, even before Granny had spoken, as though he’d sensed that Granny was behind him. He was so tall, his head knocked against a pan hanging from above.

‘Don’t mind me, I’m only sneaking a peek,’ said Granny, when the cook put out a large veined hand to shake hers. It dripped egg yolk and milk—or was that milk?

‘It’s custard,’ said the cook, reading her mind. ‘For lunch.’

He was a bulldozer of a man, a misfit in the kitchen, dwarfing even the enormous oven to toy size. He was almost doubled over the stove, and every time he moved, his elbows or his head struck something. His hair was pulled back in a topknot, slicked into place.

He was all sinew and muscle, more the sort of person who should be doing push-ups in an army camp than cooking for a school full of children. But his smile was playful and his mouth twitched at the edges, like it would break out into a laugh anytime, anywhere. And if the aromas in his kitchen were any indication, he knew what he was doing and he had fun doing it.

‘I’m just leaving,’ Granny Grit said, taking in the mess, the eggshells and the empty packets waiting to be binned. It wasn’t easy cooking for so many children, Granny knew—she had done this every day since the police had carted Chef Gretta off to jail.

She stuck her head back in as an afterthought, or maybe because another whiff of that heavenly, creamy dessert would send her floating upstairs without a care in the world. ‘What are you making?’

‘Crème brawlay,’ he said with a small smile.

It was only when Granny Grit returned to her desk and reached for the phone that she gave the cook’s reply a moment’s consideration. ‘Crème brawlay,’ he had said. Now, Granny was well travelled and loved crème brûlée. She also knew that B-R-Û-L-É-E is pronounced ‘brulay’, not ‘brawlay’. She chuckled to herself; the poor man had a problem with his French, that was all.

The extraordinarily hideous head was on the phone now. It did not waste time with niceties like ‘Hello?’ or ‘Would this be a good time to speak?’ It came to the point right away. ‘Find the Grand Plan—and fast! Or our deal is off!’

CHAPTER 2

A yellow blob of egg yolk landed on Tammy Telltale’s face, turning the caption under her photograph into a black mush. As Cook Fedro Fracas spread the day’s paper over the kitchen counter, he giggled. It was rather an odd little sound issuing from someone this large and it made him sound like a schoolkid, but the good cook couldn’t be bothered to produce a more aggressive snigger. There was something about food on face, any face, that tickled his funny bone.

Why, the first time Cook Fracas got food on his face, he’d only just been born. His arrival had produced a cry of joy from his mother, a whoop of delight from his father and a fresh flurry of activity from the doctor. But outside the hospital window, down in the streets of Ivrea, it made no difference to anyone.

You see, in this small northern Italian city that you needed good eyesight to find on a map, a battle was underway. It was nothing terrible, really—no blood, no guns—just a crowd of madcaps in medieval costume pelting each other with oranges. Yes, oranges. It’s an annual tradition.

Now, bambino Fedro had only just taken his first breath. The doctor had slapped his bottom, the nurse had pinched the goo out of his nose and he had taken a pee that made him feel wet and cold. None of this helped his mood any. So when a segment of orange came flying through the window and landed splat on his head, he bawled lustily.

In the years to come, that war-worn orange had an unexpected effect on young Fedro’s personality. Why else would he take such delight in flinging carrot puree at his parents from his high chair? Or pitching peas at his classmates? Or, worst of all, lobbing a ketchup-soaked French fry at his principal that got him a suspension from school?

Many suspensions later, Cook Fracas applied for the post of army cook because he assumed that an army mess was a place where it was perfectly all right to make a mess. If only someone had told him that an army mess is just the word for an army kitchen!

He threw tomatoes at some soldiers and one landed straight on the general’s face. At this point, you should know that a general is the army’s version of a school principal. Neither have been known to possess a sense of humour, especially when it comes to flying food. The flying tomato was the end of Fedro’s army career.

Now, Cook Fracas was beating a hundred eggs in the Horrid High kitchen. A French dessert was on the menu—crème brawlay! The cook giggled again. The real reason Cook Fracas called his cream dish a ‘brawlay’ was because it wasn’t a ‘brûlée’, which means ‘burnt cream’. It was the cook’s own invention, inspired by the English word ‘brawl’.

From what Cook Fracas had been told about Horrid High, the cook before him had been a real meanie. Now, Cook Fracas was no meanie, but he certainly made a mean dessert. He rubbed his hands gleefully. He’d leave the kids at Horrid High licking their fingers. And wiping their faces. And mopping the floor. In other words, Cook Fracas’s crème brawlay was an unholy excuse for a rumpus, a scuffle, a right and proper food fight.

He noted, with pleasure, that the yolk on that day’s paper had spread outwards, making a spongy mess of Tammy in her Sunday best. Served her right, whoever she was.

***

Upstairs in her office, Granny Grit was listening closely to the police inspector on the other end of the telephone. ‘We haven’t found every last horrid teacher, Principal Grit, but we will,’ he was saying.

Granny sighed—the whole sticky matter was giving her a headache. She’d been away from school for a long time, too long, leading the Grit Movement. If she had dreamt, even for one moment, that the happy school she’d left behind would turn into a horrid school . . .

She pinched her eyebrows with her fingers to dull the pain. And somewhere above her right brow, she found a smidge of custard that came off on her fingers. She should have washed in the basin but it would be rude to put the busy inspector on hold. Without another thought, Granny Grit licked the custard off. And even though licking food off your hands isn’t the best way to get them clean, principals have been known to do it. The custard was so heavenly, it made Granny feel like singing.

‘We still haven’t been able to get to the bottom of things, why the principal needed to throw this mad bash and call every horrid teacher,’ the inspector was saying. ‘We haven’t had any leads on the Grand Plan. Perhaps it’s best forgotten for now?’

‘As long as we don’t forget forever, Inspector,’ said Granny Grit as she rung off. History will not repeat itself as long as we remember, she thought to herself. Wasn’t that why the whip and the Throne were preserved for everyone to see? Wasn’t that why she’d insisted that the school should still be known as Horrid High?

But only in name. The old sign, the one that said There will always be consequences had been trashed. The new sign on the gate put it quite well: There will always be a home here. But turning a school around wasn’t as easy as just changing the sign on the gate—Granny knew that.

The school was a little smaller for now. Some of the old children had left, those with distant relatives or parents who’d had a change of heart after reading the newspapers and been horrified enough to come claim them. Granny Grit thought of Mesmer Martin, the dark-haired girl with hypnotic skills, and smiled. Mesmer was home with her father now and there was no better place for a child than home.

Granny hoped that Horrid High would be a home, too, for the kids who weren’t as lucky as Mesmer. Certainly, she’d done everything to make it happier. The old insulting dorm names—Lowlife, Scumbag, Nincompoop and Dimwit— had been swapped for new houses named after mythical creatures. They sounded heroic and exciting—Centaur, Sphinx, Pegasus and Dragon. The children now had real beds to sleep in; there was hot, fresh food in the dining room; the unkempt schoolyard had been transformed into a lush green playground; and the tadpole-infested tank had been replaced by a real swimming pool.

The locks on the front gate had been removed and the Tower of Torture had been turned into the Tower Library. A reading nook perched high above the ground, the Tower Library had books, a slowly growing news archive and a cosy corner filled with bright, plump cushions.

In Granny’s classroom downstairs, the heated discussion of the day’s news would have petered out by now. But just as Granny Grit rose to leave, the phone on her desk rang again. Abella! It had been ages! This young Spanish animal lover had been with the Grit Movement for five years now. But Abella was saying something that made Granny’s smile flicker and fade. Her eyebrows shot up, worry lines appeared on her forehead and in a choked voice, she gasped, ‘Oh dear!’

It was a quick conversation—the connection from Puerto Maldonado in Peru was a weak one. ‘Terrible things going on in the Amazon . . .’ and then phone static. ‘I’m going undercover . . . something very dangerous . . .’ More static. ‘Some cunning plans are afoot.’ And although Granny shouted ‘Be careful!’ more than once, she was drowned out by a fresh burst of static and then they were cut off. There was so much horridness in the world . . . but then Granny smiled weakly as she remembered her children in the classroom downstairs. At long last, there was one tiny place on earth that was horrid-proof.

Granny Grit lingered near the telephone for a few more minutes, just in case Abella called back. The list of new teachers caught her eye. Dr Bloom was coming in to teach ‘hands-on science,’ she’d said over the phone when Granny Grit interviewed her, ‘the sort of science that gets under your fingernails—plenty of experiments and field trips!’ Granny Grit loved the idea. Education didn’t make sense if you were caged in a classroom all day, reading in books what you could see, smell and touch for yourself outside.

Nita Nottynuf would take maths and although she was still a little rough around the edges, Granny Grit knew Miss Nottynuf would settle in. It was never easy growing up being told that you were less than everyone else, and what Miss Nottynuf needed was time to heal.

Colonel Craven, the new sports teacher, was an army hero with many medals to his credit and he’d recommended Cook Fracas too. Granny had a good feeling about the colonel. His right eyebrow twitched several times without reason and his left arm jerked up without cause but those were nervous tics, that was all. If you’d escaped from an enemy camp after months of captivity, you’d be nervous too.

The phone rang again. Abella—it had to be! Granny Grit grabbed it on the first ring but the voice on the other end was a tremulous one. Granny knew it only too well. ‘Mrs Telltale!’ said Granny, wishing that Mrs Telltale would go someplace far away with a poor phone connection. Someplace like Puerto Maldonado, Peru.

But oh no, Mrs Telltale was threatening to do quite the opposite. ‘Grandma Grit,’ she started, making Granny grimace. ‘Tammy and I thought we’d drop into school for a few days, Tammy so misses her friends!’

What friends? It was an ungracious thought for a school principal, but principals have been known to have those too. ‘Just a quick catch-up, you know,’ Mrs Telltale was saying, ‘before we go off on book tour again? We could pencil it into our diary?’

But Granny Grit leaned across her desk to make a red circle on her calendar two weeks down. Mrs Telltale’s next call! she scribbled next to it. Avoid at all cost!

Mrs Telltale was still talking. ‘Tammy’s on a TV show . . .’

The lunch bell rang. Not the wailing sound that had heralded the hour at the old school but a cheerful chime that was music to hungry ears.

Alas, Mrs Telltale’s tall tale had no end in sight. Granny felt a weariness take hold of her. She felt grateful all of a sudden for the large man in the kitchen downstairs. Being principal and cooking for a hundred hungry children was too much, even for her.

CHAPTER 3

A hundred hungry tummies rumbled when the lunch bell rang. For Phil, the thought of food drove away all other concerns. The day’s news was old and had already been chewed on. Lunch, on the other hand, was fresh and tasted much better.

Ferg and Fermina were in the middle of a heated discussion about a news story on page twenty-two. ‘What makes you think that this doesn’t deserve to be on the front page?’ Fermina demanded.

‘The fact that there are at least three other stories that deserve it more?’ Ferg said. ‘Let’s just agree to disagree, shall we?’

Fermina gave a tight nod, flinging her braids from front to back and pretending that disagreement was fine with her. In truth, though, her feathers were a little ruffled. These days, Ferg was being positively annoying!

Ferg tried hard not to laugh. Fermina looked so funny when she was in a huff! ‘Come on, Ferm, don’t take it personally—ouch!’ Phil had pinched Ferg’s arm. ‘What did you do that for?’

‘To remind you that there’s more pain coming if we don’t go to lunch this instant!’ said Phil.

‘I’ll tell Granny Grit that you held us up, Ferm and you!’ added Immy, her dimples flashing to indicate that she was only half serious.

Fermina collapsed into giggles at that, forgetting her sullen mood of a moment ago. ‘Let’s go, quick, before Immy turns into Tammy!’ she cried, slapping Ferg on the back a little harder than she needed to and quite enjoying it.

Upstairs, Tammy’s mother was on the verge of delivering her 173rd sentence in five breaths flat when she stopped. Had she finally run out of air—or words? Granny didn’t waste a minute to consider this. She had been given a glorious opportunity to cut in—ah, and the perfect excuse! There was a car pulling in at the school gates. ‘I must go, Mrs Telltale,’ Granny cried. ‘We have unexpected visitors!’

As she rung off, Granny’s heart exulted. The school hadn’t had any visitors in a while, and they couldn’t have come at a better time! They drove a fancy red convertible, the sort where the roof slides back and you can drive with the wind tugging at your hair. Oddly, though, the roof was down, the windows were up and the occupants seemed quite unaware of what a beautiful day it was. As a man and a woman got out of the car, it became evident why.

They were squabbling, their voices loud enough to be carried on the breeze, though Granny could not catch what they were saying. The man slammed his door. The woman slammed hers. The man was dragging a young boy out of the backseat. The woman was dragging another one out. The man was shaking his fist at the woman. The woman was shaking her fist right back. They were slugging it out, point for point, like kids in a schoolyard scuffle. The two boys who trailed behind them were behaving more grown-up, wearing the sort of expression indulgent parents do when their children misbehave.

If the four visitors had bothered to look up at the school, they might have wondered how Horrid High could ever have been horrid, with its sparkling red roof and spanking white walls. They might have noticed the green window from which an old lady was staring down at them, looking incredibly sad that there were parents in this world who had no qualms about fighting in front of their children.

The warring parents were so busy trading insults, they hurried past Ferg and his friends in the hallway without lowering their voices. ‘It was your idea to have them!’ the man was saying.

‘And I suppose it’s a bad idea just because it’s mine?’ countered the woman.

‘Not one, but two!’ said the father, heading for the stairs with a renewed burst of speed as though he wanted to get away from his family. ‘What is it with you and pairs?’

‘You make it sound like I miscounted!’ It was the mother’s turn now. She matched him, step for step, propelled by her anger. ‘Hurry up, boys!’

Why were they talking about their kids like this, plain enough for everyone to hear? Ferg’s cheeks were burning. The visitors reminded him of his own mom and dad, as clearly as if he had held up a family photograph. ‘Should have got a dog instead, I told you,’ the man was muttering as they clattered up the stairs.

The newcomers had dampened everyone’s mood. The kids couldn’t help feeling sorry for the boys. Fermina dug her little hands deep into her pockets and shuffled faster towards the dining room. Immy picked at her cornrows and ran her tongue over her new braces. Phil kept his face expressionless, but it bothered him, too, and made his heart beat a little faster. Parents! Who could understand them?

One welcoming look from Granny Grit pottering about the kitchen would have driven away every last dark thought. Granny Grit was not in but the aroma greeting the children made up for it quite well. The children stopped short, they had quite forgotten! Hadn’t Granny mentioned that there was a try-out this week for the job of school chef?

Perhaps they had imagined someone like Granny, lean and spry, with twinkling eyes and a ready laugh. The new cook was a good deal taller, his chef’s hat grazing the doorframe. With massive shoulders, a neck as solid as a block of wood and a hard, square chin from which a patch of dark hair was sprouting, he looked like he could be standing beside a battering ram on some medieval battlefield, giving a war cry.

Only, there was no castle to attack and no walls to be breached—just a humongous pot full of something that smelt heavenly, sealed off on top with a dark-brown crust. ‘That’s a crème brawlay!’ Cook Fracas was saying as the children entered. ‘The only thing that lies between you and that creamy custard is the burnt sugar on top! Mmmmmmmm!’ And here he stooped low to take a huge whiff. ‘It smells delightful, doesn’t it?’

The children nodded mutely. You see, it’s physically impossible to inhale and speak at the same time, try it and see. And at this moment, the children were inhaling huge lungfuls of the heady aroma. It sailed into their mouths and settled in their stomachs.

As if reading their thoughts, Cook Fracas held up a large kitchen hammer.

‘Who’ll have first go?’

Confounded looks were exchanged—first go at what? ‘Go on, shatter the crust if you want what’s below!’ said Cook Fracas, pointing at the pot. ‘Who’ll go first?’ and now his eyes wandered around the room, settling tentatively on one face, then another. ‘You?’

The children turned at their tables, tracing a line from the cook to the person he was looking at, all the way to the back of the dining room. To the very last table where a large girl sat alone. As she always did. Volumina Butt.

‘Yes, you!’ the cook nodded, tapping the palm of his hand with his hammer as though he were keeping time.

Volumina glowered at the cook and kept sitting.

‘Come on up here!’ Cook Fracas persisted. ‘You look capable of doing the job!’

Volumina narrowed her eyes and glared at the cook, rising slowly. ‘Are you calling me fat?’

A tremor passed through the room, from child to child, like a ripple in a pond. No one would call Volumina fat! Not because she wasn’t but because no child would like ‘You’re fat!’ to be his last words. Volumina could sit on any child at Horrid High and snap him like a twig. She didn’t need to be told she was fat—she knew.

‘I’m calling you strong,’ said the cook gently. His words disarmed her a little.

‘I don’t feel like it!’ she mumbled, ‘I can’t!’ And she promptly sat down, hard enough to make the bench shudder.

‘Why not?’ Cook Fracas persisted. The girl winced and shook her head.

‘I’m waiting,’ said the cook, and now his solemn mouth melted into a gleeful smile. ‘Come on, try, it’ll be fun!’

All eyes were on Volumina now. She could have sat on the cook and flattened him if she wanted to—she was still the school bully, even if her bottom hadn’t settled on anyone this term because there were no new kids yet. But hadn’t the cook promised that this would be fun?

The bench groaned as Volumina rose again and everyone watched, curious and confused, as she lumbered slowly to the centre of the room. She peered into the dish. The golden brown crust glistened. It was rather an odd request. Why go to the trouble of shattering something that looked so flawless?

But Cook Fracas was giving her a nod now and issuing a battle cry: ‘BREACH THE BRAWLAY!’ The hammer was heavy but Volumina swung it easily.

Kerrrrchanggggg! The sugar crust came apart like the ground during an earthquake. ‘BREACH THE BRAWLAY!’ Volumina swung again. Kerrrrchanggggg! The crust ripped like a shirt caught in a doornail, top to bottom, and shards of sugar went flying. ‘Ooooooh!’ groaned a girl where the crust had grazed her cheek. ‘BREACH THE BRAWLAY!’ Kerrrrchanggggg! Now the jagged, sticky sugar projectiles were flying like arrows, splintering against chairs, ricochetting off walls. The children dived for cover (or to taste the sweet slivers where they had landed on the floor, sparkling like ice). Kerrrrchanggggg! Kerrrrchanggggg! It was snowing sugar now!

‘It’s stuck to my hair,’ a girl cried, trying to pry bits of sugar loose. ‘It got me on the forehead!’ exclaimed a boy who hadn’t ducked in time.

‘Bravo!’ shouted Cook Fracas, bringing his hands together like a monkey crashing cymbals. ‘Bowls and spoons, kids, for the custard! Dig in! I’ve kept some sandwiches out on the counter too!’

Volumina didn’t need to be told twice; she treated herself to an extra-large helping of everything. All that hammer- swinging had only whetted her appetite.

A clamour of kids edged closer to the brawlay pot, plucking up the courage to move in after Volumina had finished. Moods were a little on edge, tempers frayed, and a few kids elbowed each other for a long-delayed lunch. At the corners of the room, minor spats had broken out. A few fragments of caramelized sugar were hanging from the ceiling now, like a chandelier. The ground was a sticky trap. Cook Fracas brought his hands to his lips, blew kisses everywhere and trilled, ‘Benissimo! Sopraino! ’

Ferg had no idea what ‘benissimo’ meant, or ‘sopraino’—he wasn’t Italian, after all—but the English translations of these words popped in his head like fireworks on New Year’s Eve. Excellent! Marvellous! Incredible! Were there any other words to describe how wonderful Cook Fracas’s brawlay tasted?

‘Here! Under the table!’ he hissed, calling Fermina over and tugging at Phil’s trouser leg as he made his way through the sugary mess, bowl in hand. ‘New seating arrangements?’ panted Immy, ducking and sliding next to Ferg to make place for the others. ‘Too much sugar flying!’ said Fermina, squeezing in and cringing as a pair of sandals skidded on sugar, their owner flailing in the air before crashing to the ground. ‘I’ve never seen anything like this,’ sputtered Phil between mouthfuls of smoked salmon sandwich. ‘The new cook is mental!’

The mess and the madness overhead faded into silence as the children ate. None of them had dined in fancy French restaurants, but you don’t have to be an expert on food to know when something tastes good. This brawlay was beyond good. The sandwiches weren’t bad either. They certainly beat Chef Gretta’s rat-tail ratatouille! And although Granny Grit’s cooking had the wholesome flavour of anything prepared with love, the children knew that Granny couldn’t be running the kitchen forever. As principal of Horrid High, she had more on her plate than just food.

During that particular lunch hour, what Granny had instead of a plateful of food was an office full of unannounced guests—two squabbling parents, two sulking children—oh, and four chihuahuas in panic mode. You see, Mr Brace had knocked imperiously on the door mid-rant. Granny’s ‘Come in!’ had interrupted him as he enumerated to Mrs Brace the many ways in which dogs are better than children. So when he pushed open the door and his foot narrowly missed a chihuahua—‘THERE! That’s what we should have had!’—he triggered a chihuahua crisis.

Hider, the shy one, skittered about and collided into Teacup, who had had a narrow brush with death under Mr Brace’s giant foot and was feeling jittery anyway. Bella disliked loud voices and Mr Brace had raised his voice on ‘THERE’, making her jump. The three of them stood up on their hind legs and looked longingly at the pink, polka-dotted bag on Granny’s desk. Tortilla was a canny survivor who knew that there was safety in numbers and joined right in. They matched howl for howl and yowl for yowl till Granny lowered her handbag to the ground. The bag juddered as they all disappeared inside it, and Granny Grit set her mouth in a thin line and said, ‘Now, how can I help you?’

Her question released a torrent of words, Mr and Mrs Brace both speaking at once in great agitation. Now, Granny Grit had had more than her day’s share of ravers and ramblers. She turned to the two miserable boys, her face softening—‘Would you please wait outside while I speak to your parents? If you’re lucky, you’ll meet our school pet. He’s a darling little white mouse called Saltpetre, I’m sure you’ll love him. He’s scuttling about in the hallway somewhere.’

As soon as the boys had left the room, Granny Grit instructed Mr and Mrs Brace like insolent children who had spoken out of turn. ‘Start again, please, from the beginning, and speak one after the other.’ They had a long list of complaints against each other and against their boys, which now took twice as long because they weren’t speaking in unison.

When Mr Brace was halfway done, Granny glanced at the clock. ‘Have your sons eaten?’ The Braces exchanged puzzled looks. ‘Wha . . . Didn’t you feed them?’ cried Mrs Brace. ‘You didn’t tell me to!’ retaliated Mr Brace. Amidst all the finger-pointing, Granny popped out to tell the boys, ‘Why don’t you head down those stairs to the dining room? If you’re lucky, there’ll still be some lunch left over. We have a new cook.’

The new cook was whistling Funiculi Funicula, which is a popular Italian song about a funicular that once chugged its way up Mount Vesuvius. The cook’s crème brawlay had done as much damage to the kitchen as the volcanic eruption on Mount Vesuvius that ultimately destroyed the funicular. But this was a jaunty song and it was putting Cook Fracas in a jaunty mood. Even if the poor kids who had to clean up that afternoon didn’t feel as, well, jaunty.

Fermina was on all fours, teasing a stubborn crust of sugar off the floor with her fingernails. ‘I wouldn’t have eaten so much if I’d remembered that I was on duty today!’ she groaned. Ferg grunted in agreement. He had been swabbing the same sticky patch for ten minutes to no avail.

Fermina bit her lip thoughtfully. She felt bad whining about cleaning up. The kitchen was in a shambles but their bellies were full of good food. That had to count for something.

‘Well, hello!’ said Cook Fracas, ‘You’ve missed all the fun!’

The children looked up. The boys were standing at the door of the dining room, looking perplexed.

‘We have some brawlay left over if you’re hungry,’ said Cook Fracas, smiling broadly. ‘Your principal has missed lunch—I’ll take some of this up to her as well.’

The boys eagerly fell upon the two bowls of brawlay, eating as though they had been starving for days. Ferg shot Fermina a meaningful look. It wasn’t that far back in time that they’d been famished like this.

The boys looked so alike, Ferg found himself staring and rubbing his eyes, just to check that this wasn’t a case of double vision. They were tall and wiry, with clear faces, eyes that turned up at the corners and bushy brows. A thick lock of their dark hair flopped down over one eye, giving them a mysterious look. They were dressed the same, too, down to the last detail. When the boys looked up and caught Ferg staring, one introduced himself.

‘Mallus!’ he said, raising his left hand in a small wave. ‘And he’s Malo, short for Malcovich!’ His twin scratched his right cheek in a sheepish gesture.

‘Are you both staying?’ asked Fermina, suddenly conscious of the pimple growing on her chin. She tried to hide the eagerness in her voice. Everyone was missing Mesmer and their gang could use two more friends, that was all.

The twins shrugged together in a well-timed gesture: ‘We’d like to!’

When Cook Fracas returned, he didn’t look pleased to see Ferg and Fermina taking an unscheduled break. ‘Back to work, kids, it’ll be time for class soon!’ he said. ‘Boys, are you on clean-up too?’

Malo and Mallus shook their heads. ‘Oh, you’re the new boys!’ cried the cook, remembering the noisy guests in Granny’s office. ‘Off you go then—out, you’re wanted back upstairs!’

The twins threw small smiles at Ferg and Fermina as they left. ‘I hope they stay!’ said Fermina, staring after them. Ferg returned to the stubborn stain with renewed energy. His ears were tingling, as they normally did when something was about to go wrong. Now where was that tissue box? There! Ferg blew his nose and his ears popped. He felt relieved. It was only a cold, that was all.

CHAPTER 4

Granny Grit closed her eyes and blessed Cook Fracas. The delicious crème brûlée had warmed her up inside. She’d have liked to eat it slowly. She’d never understood why some people treated food like it had legs and would get away if they weren’t fast enough to grab it. Food was meant to be savoured.

But a car door slammed downstairs. The Braces had come to Horrid High with their minds made up. They were only too eager to unload both suitcases and children so that they could speed off into the horizon to freedom at last!

‘Get a dog . . .’ Mr Brace had said, his eyes lighting up at the hopeful thought. ‘Get a life . . .’ Mrs Brace had said, glaring at Mr Brace.

Granny Grit exhaled slowly. When the twins came up, she would have to break the news to them. Their parents had bolted without waiting to say goodbye. The phone rang a few more times and stopped. It was likely Abella from Peru, trying to get through. She glanced at the clock—it was too late to resume that lesson she’d left halfway. There was so much to teach the children, she feared she was falling behind. But the children were probably in Miss Nottynuf ’s maths class by now.

Fractions were making everyone feel rather fractious. Cross, in other words, and irritable. How could 3/6 and 4/8 be the same thing? Yet, if Miss Nottynuf was to be believed, they were!

‘Oh dear, I’ve not been very good at explaining this, have I?’ Miss Nottynuf hunched her shoulders, swept her fine hair back from her face and turned to the board.

3/6 = 4/8 = 5/10.

Her hair was so soft and straight, it sprang loose again. She blinked hard at the class through her thick spectacles. ‘Do you see a pattern in these numbers?’

It was obvious to nobody but Phil. He grinned from ear to ear. ‘All these fractions are different ways of expressing a half!’ Miss Nottynuf shot him a wan smile. But as her eyes swept over the puzzled faces in the room, her smile faded and a shadow crossed her face. ‘Yes, no matter how you express half, it’s a miserable little fraction, isn’t it? Half and not whole.’ She walked to the window for a moment, deep in thought. Her shoulders sagged as she remembered her parents and how they had always made her feel half as good as any other child.

‘It’s not good to be half, you know.’

‘I’m not sure I understand any more!’ said Phil, dismayed. No one did. How could fractions have feelings? This was

a maths class, and Miss Nottynuf did not seem to be sticking to the subject.

‘Oh, yes!’ she said, looking at Phil with a sad light in her eyes. ‘No one cares about you if you’re not whole. There was a little girl whose life was measured in fractions . . . Let’s call her Nita, shall we?’

Miss Nottynuf wrung her hands. ‘Nita was half as beautiful as her mother, half as clever as her father and half as athletic as her brother!’

The maths teacher stopped again, hugging her narrow shoulders and shivering.

Phil opened his mouth to interrupt Miss Nottynuf when Immy nudged him. Sad people needed their silences—Immy knew that much. She remembered her father’s long silences during his ventriloquist shows at the circus and how they made the audience restless. ‘Go on, will you?’ they’d shout. Phil would just have to be more patient. Miss Nottynuf was giving ‘half ’ a whole new meaning by telling them her own sad story.

‘What happened, then, Miss Nottynuf?’ blurted a scruffy boy in the middle row with a runny nose.

‘Well, Nita’s heart broke in half with all that scoring, and she walked around forever with a hole inside her, right in the middle, like a big zero! It was the missing bit of Nita, the one without which she would never be whole.’

Miss Nottynuf was blinking back tears now and there was an awkward silence as everyone pretended not to notice that the maths teacher was crying.

‘I’m sure the class wasn’t good enough and I’m so sorry about it!’ she said, sounding choked up as the bell rang. With a last smothered sob, she was gone.

Later that night, the children met in the common room of Ferg’s dorm. It used to be called Scumbag but these days, it was known as Sphinx House.

Things had changed so much for the better. These had only been empty spaces earlier, but now, all the kids flocked to their common rooms when classes were over. The common rooms were home, even though most of the kids at Horrid High were a bit foggy about what home meant.

‘I’ll get you started,’ Granny Grit had told each house, throwing in comfortable sofas, a few beanbags, large floor lamps, a bright rug and an enormous bookshelf to transform each common room into an inviting place. ‘The rest,’ she said, ‘is up to you!’

The children were given a house allowance to spend at one go, or slowly. Sphinx House had splurged on a games corner; Dragon House had an art wall that they redesigned every three months; Centaur House prided itself on having wangled a small refrigerator stocked with midnight snacks; and Pegasus House was still mulling over what to spend its allowance on.

Ferg, Fermina and Phil were sitting on beanbags in one corner. Fermina was wondering where Immy was, when she burst in, giggling. ‘The new boys are in my house!’ she said, popping back out and pushing the twins in.

The twins were painfully shy. Dressed in identical checked pyjamas, they stood awkwardly just inside the doorway. Immy could barely contain her enthusiasm and prodded them from behind. ‘Go on, they’re my best friends here!’ she urged the twins. ‘Ferg, Fermina and Phil!’

‘We’ve met,’ said Fermina with a solemn nod although she wanted to jump for joy. New friends—and they were pretty cute too! Phil moved over, plumping the throw-cushions and restoring them to fullness. ‘How are you settling in?’

‘Just fine,’ mumbled Malo, massaging his right eyebrow with his finger.

‘Thanks!’ interjected Mallus, tugging at his left ear.

Ferg, who hadn’t spent any time around twins, couldn’t take his eyes off the boys. They smiled very little, he noticed, and their conversation skills were poor. He recalled their squabbling parents—it was no surprise the twins weren’t comfortable around new people. Hadn’t he been the same way, all but invisible, till he got to Horrid High and made friends? It wasn’t easy having parents who treated you like a giant mistake.

‘I wonder where Saltpetre is!’ said Immy brightly as though she sensed what everyone was thinking and wanted to change the subject.

‘Our school pet is not allowed into class, you see,’ explained Phil to the twins, ‘and he misses us terribly!’

‘Not today, though!’ said Fermina, laughing in an exaggeratedly high voice. ‘Maybe he’s found better company!’ Ferg frowned. Fermina was behaving a little daft around the twins. She was beginning to remind him of those giggly

girls at his old school who made his hair stand on end. ‘It must have been wonderful growing up as twins,’ said Immy. ‘Tell me, are you absolutely and totally identical?’

‘We are!’ the twins cried, a little quickly. ‘Our mother always liked identical pairs!’

‘She must have adored you!’ gushed Fermina.

The twins’ voices dropped. ‘She did, until she found us a little disappointing . . .’

If the twins had divulged more, if the children had pressed further, the story of Mrs Brace’s love for twos would have emerged. Mrs Brace loved things that came in pairs, especially identical pairs. It was silly, how Mrs Brace bought two copies of the same book or two blouses of the same colour, or how she always knocked on wood, twice, for good luck. Mr Brace was in love with Mrs Brace then, and when grown-ups are in love, even silly things are forgiven.

Mrs B had no way of knowing that she would have twins, or else she would have skipped (two steps at a time, mind you) for all nine months. But right before the twins were born, Mrs Brace was possessed by a sudden craving for Chinese food. Perhaps it was the thought of those identical chopsticks—we will never know—but off they went, Mr and Mrs B, to the best Chinese restaurant in town. After dessert, when Mrs B bit into her second fortune cookie, she gasped. For the message inside both cookies was the same: Good things come in pairs. This could mean only one thing, and Mrs Brace was sure of it. ‘Twins!’

She would have given them the same names, but that would have been rather silly, even for Mrs Brace. So instead, she named them Mallus and Malo, and she dressed them so that they couldn’t be told apart. ‘My two peas in a pod!’ she told everyone proudly. She read them the same story every night: Noah’s Ark. ‘Two elephants, two zebras, two hippos went into the ark . . .’

When the twins were in their terrible twos, Mr Brace bought them their first set of crayons. Two identical sets. And to Mrs Brace’s utter dismay, she discovered that her precious boys weren’t identical. Almost identical. But almost wasn’t good enough for Mrs Brace. Just as it hadn’t been good enough for the Nottynufs.

Mrs Brace fell out of love with her twins just as fast as she’d fallen in love with them. She stopped reading them Noah’s Ark. She stopped telling everyone about her two peas in a pod. That is, perhaps, where all the twin trouble began. And Mrs Brace concluded that you can never trust a cheap fortune cookie to reliably tell your future. Good things most certainly do not come in pairs!

But of course, Ferg and his friends heard nothing of this twosome tale because just then, a boy with long hair found Funiculi Funicula on the radio.

‘That’s the tune Cook Fracas was whistling this afternoon!’ Ferg leapt up, pulling Fermina to her feet. ‘Let’s dance!’

‘I won’t be caught dead dancing with a boy!’ said Fermina, whirling about the room with him nonetheless, her braids flying.

‘I have two partners now,’ cried Immy, pulling the twins to their feet. ‘Phil, can you manage?’

But Phil wasn’t the dancing sort. He sat back, head against his hands, and guffawed. Dinner had been carrot soup, olive bread and piping-hot samosas. His friends were crashing about the room like baboons. The twins were laughing now because Immy was teaching them to jive. His heart felt as full as his stomach. All was well, apart from the brouhaha over the brawlay, of course—and they would tell Granny Grit all about it. But not today. Today was for new friends, new teachers, a new school and new experiences. Today was about being happier than all of them had been in a long, long time.