Sneak Peek: Wisha WozzariterContemporary Fiction

Wisha Wozzariter loved reading. She read before school and after school. She read before lunch and after lunch. She read before dinner and after dinner. She would have read all day and all night if she could.

Wisha hated bad books, but she hated one thing even more: good ones. Good books always left her feeling she could do better if she were to write a book of her own. She’d put down a good book, sighing, ‘Now that’s a book I could have written.’

On her tenth birthday, Wisha read Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. She hated it more than anything. There was no reason something this good should not have been written by her. She got to the last word on the last page, then sighed, ‘Now that’s a book I could have written!’

‘Why don’t you?’ said a green little worm, popping his head out of page no. 64.

‘Who are you?’ asked Wisha, startled.

‘Why, a Bookworm, who else?’ said the worm, sounding surprised. ‘I’ve heard you say the same thing after every good book. So why don’t you?’

‘Why don’t I—what?’ said Wisha.

‘Write a book, write a book,’ said the Bookworm in a sing-song voice, wriggling his way out on to the cover.

‘I wish I was a writer,’ sighed Wisha.

‘Well, you are Wisha Wozzariter,’ said the Bookworm.

‘So I am! But I don’t quite know where to begin.’

‘At the beginning, of course,’ said the Bookworm, rolling his eyes. ‘Got some time?’

‘Yee-es. Why, what do you suggest?’ asked Wisha.

‘A trip to the Marketplace of Ideas,’ said the Bookworm. ‘My treat.’

Wisha jumped up. ‘Sounds more exciting than wishing all day! How do we get there?’

‘Close your eyes and hold my hand tight,’ said the Bookworm. ‘We’re catching the Thought Express.’

‘When does it come in?’ asked Wisha.

‘Don’t know. Are your thoughts always on time?’ ‘Not really.’

‘Well, then, we might have a little wait ahead of us,’ said the Bookworm. ‘It would help if you were to say your name to yourself a few times.’

So Wisha closed her eyes and said, ‘Wisha Wozzariter, Wisha Wozzariter, Wisha Wozzariter.’

The Thought Express was a little slow and a little late, but it came in, sure enough. And when it left for the Marketplace of Ideas, Wisha and the Bookworm were on it.

The Marketplace of Ideas

‘Looking for ideas?’ asked a scrawny young fellow in a loose brown coat, with more pockets than it had buttons on it. ‘Big ones? Small ones? I specialize in small ones.’

Wisha stared at him in disbelief, and then all around her in bewilderment. The marketplace was a complete mess. She did not think there was a clear idea to be found here. Some vendors stood outside their stalls, on tall stools, shouting out their wares. Others, like the skinny specialist of small ideas standing before her, mingled with the crowd. Buyers jostled with sellers.

‘New ideas for old! New ideas for old!’ cried a woman dragging a bag full of polishing rags behind her. ‘I repair old ideas. I shine old ideas. I recycle old ideas. Nothing is so old it cannot be made new.’

Pickup vans filled with ideas blared their horns impatiently. A garbage-collection truck trundled along. ‘Don’t litter the roads with your tired, old ideas. Deposit them here!’ it said on the side of it.

At one stall, a bearded artist kept picking up bottle after bottle of ideas, uncorking the lid and sniffing at the mouth. ‘Just doesn’t smell like a masterpiece,’ he grumbled.

A handcart stacked with cages of ideas tried to make an uncertain path through all the pell-mell. It tipped over, the cages skittering across the pavement and one cage door flying open. Out staggered a baby idea, squawking like a chicken before flapping its wings and taking flight.

A red-haired man immediately jumped off the handcart, holding his head and running behind the baby idea. He tried to clutch at its legs, but it was too high up in the air already. ‘My idea, my idea!’ he cried, almost hurtling into Wisha. ‘It’s escaped me.’

‘Get a grip,’ droned a salesgirl standing outside the IdeaMart. ‘We’re open 24×7,’ she said, as if by rote. ‘We never run out of ideas. Lost an idea? Get another here.’

She was not the only one selling ideas. Neon advertisements hung overhead. A plane made its arc across the sky, leaving a jet trail behind that read: For ideas that really take off, call 1-800-IDEASHOP.

Wisha was so busy looking up at the sky, she didn’t see the pail of water being sloshed out on the street. Before she knew it, she was dripping wet. ‘Get out of the way!’ said a boy crossly, the empty pail still clanging in his hand. The other boys gathered around him, giggling. ‘Don’t you know better than to wander down New Idea Street, looking up at the sky?’

The Bookworm nudged Wisha along before she could retort. ‘They’re clearing up the old ideas here to make place for new ones,’ he said. ‘Better not to fight them unless you want a bucket of old ideas to be emptied on your head!’

Wisha moved ahead, reluctantly. At the end of the road, she could now see what appeared to be the gloomiest building she had ever set her eyes upon. Dark spires reached up to the sky; the black stone walls had no windows; and in front, huge iron gates stood locked, with four guards in front of them.

‘Is this a prison of some sort?’ she asked the Bookworm.

‘It is,’ he nodded nervously before ushering her past it. ‘Bad ideas are kept in custody here. Like Slavery, for example. That has been one of our worst offenders. Keeps trying to escape under the guise of Racism.’

‘You mean Slavery is serving time here?’

‘Yes, and so would War if we could have our way,’ said the Bookworm. ‘Trouble is, the world isn’t ready to get rid of some bad ideas.’

This was all too much for Wisha to take in at one time. ‘Where are we?’ she asked finally, in total disbelief. ‘You mean to say, every idea in the world is found here? Sold here?’

‘Not sold,’ said the Bookworm, shaking his head firmly. ‘Exchanged. You must give them one idea in exchange for another.’

‘Am I going to get my ideas here?’

‘You could—but I’m taking you to a better place. Come along, we better hurry or else the best ideas will be gone.’

With that, the Bookworm pushed Wisha down New Idea Street, past Old Idea

Souk and over the Bridge of Ideas to the biggest event of the marketplace.

‘This is where the best ideas are exchanged,’ he whispered to Wisha as they stepped in.

The Grand Idea Auction

‘Anyone for an idea to make pots of money?’ bellowed the auctioneer.

Most of the people in the audience raised their hands. Wisha and the Bookworm didn’t.

‘A hundred ideas in exchange is the starting price here,’ said the auctioneer. ‘Not a bad price for something that will make you rich.’

‘Two hundred, I say,’ said an old lady with short, wispy hair, sitting in the back.

‘Three,’ immediately followed a bespectacled man seated next to Wisha.

‘Four,’ countered a little girl seated next to her mother.

And so it went, one price beating the next, till that money-making idea was sold—for 1,000 smaller ideas!—to the old lady.

The next item on sale was an idea to get famous. 10

The Grand Idea Auction

Once again, almost everyone was bidding, except Wisha and the Bookworm.

‘How about this? An idea to change the world!’ shouted the auctioneer. Wisha shot up her hand, but the Bookworm caught it in time, forcing it back down.

‘Didn’t I tell you to wait?’ he said.

‘But all we’ve done is wait,’ she said, impatient now. ‘This sounds like a good idea to me.’

‘It is—for someone who wants to change the world. You said you wanted to write, didn’t you?’

This made no sense to Wisha. ‘Of course I do,’ she said. ‘But don’t writers change the world?’

‘They might,’ said the Bookworm. ‘But they don’t write to change the world, any more than they do to make pots of money or to get famous. This idea is of no use to you.’

Wisha waited as idea after idea fell under the hammer. Idea to save the environment went for 3,000 smaller ideas; idea to move the hearts of men went for 2,000. Then it came, the idea the Bookworm had been waiting for.

‘Are there any takers for this one?’ said the auctioneer, looking doubtful as his surly assistant held up what looked like a deflated red balloon.

‘It was once sold to Lewis Carroll, who held on to it for years. But our last buyer returned it to us, saying it doesn’t work any more.’

‘Ladies and gentleman,’ he said, ‘May I present the Imagination Balloon?’

There was silence in the audience.

‘Umm . . . It does have antique value,’ ventured the auctioneer, but not one of them raised their hands.

‘Now!’ said the Bookworm. ‘Tell him you’ll have it.’ Wisha shot her hand straight up. ‘Me! I’ll have it!’ Wisha should not have looked so eager.

A sly look spread across the auctioneer’s face.

Stroking his curly moustache, he said, ‘And what will you give me in return?’

‘I always have plenty of ideas, how many do you need?’ Wisha asked.

‘Hmmm,’ said the auctioneer. ‘Not ideas, we have enough of those by now. Tell you what, give me a bottle of Inspiration.’

Wisha tried to reply, but the Bookworm cut her short. ‘Come now, a bottle is too much to ask of a first-time writer, you know that! We’ll give you half a bottle, or you can find yourself another buyer.’

The auctioneer leaned back, narrowing his eyes. ‘You? Still after the Imagination Balloon when it did precious little for that fellow you brought with you the last time?’

Saying that, he brought the hammer down with a resounding thud. ‘It’s yours. The Imagination Balloon is yours for half a bottle of Inspiration, to be delivered to us by the end of this year.’

So that was how Wisha Wozzariter took her Imagination home with her, although there was no instruction booklet on how to use it.

The Imagination Balloon

‘It doesn’t work!’ cried Wisha in dismay for the umpteenth time. Try as she might, she could not inflate the Imagination Balloon. As for Bookworm, he had disappeared into one of the books on the shelf and hadn’t come out in days.

Wisha picked up Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird and started reading. Only midway, she sighed, ‘I wish I was a writer. I could do better than this.’

‘Why don’t you?’ said the Bookworm, sticking his head out of page 11.

‘Well, there you are!’ said Wisha. ‘What do you mean, leaving me all alone like that with this red balloon?’ ‘You’re not alone,’ said the Bookworm. ‘Don’t you have yourself to keep you company?’

Saying that, he handed Wisha a sheet of black paper with a white door drawn in it. It said ‘SOLITUDE ONLY—OTHERS KEEP OUT!’

‘What’s this?’ Wisha began to ask, but the Bookworm was already gone.

Wisha turned the sheet of paper over. It had the door drawn on both sides, the door-knob sticking out of the page like a walnut. She closed her fingers around the knob and opened the door.

She stuck her head in, although it was a tight squeeze. She couldn’t see a thing. It felt cramped. She hesitated—it didn’t make any sense. Nothing did. Then, she stepped inside, pulling the balloon into the room with her. The room seemed to expand to make space for her and the balloon. And then the door swung shut.

Inside, it was dark and silent, except for the sound of Wisha’s thoughts, whooshing and whishing through the air like paper rockets. She put the balloon to her lips and started blowing.

It was hard going. At first, nothing happened. Then something clattered into the balloon. An orange bicycle.

‘Where did that come from? From inside me?’ wondered Wisha.

Next came the clinking sound of a bunch of metal keys. Wisha could see them through the skin of the balloon.

Then, nothing. She blew till she was blue in the face, but the balloon wouldn’t get any bigger.

Pulling the door open, the Bookworm stuck his head in. ‘Any luck yet? What’s this?’

Wisha showed him the bicycle and the metal keys, trapped inside the balloon.

‘Your Imagination isn’t throwing up too much,’ observed the Bookworm. ‘Perhaps you haven’t been keeping your eyes open.’

‘It’s not as though I walk about with my eyes shut, you know,’ retorted Wisha, growing a little weary of the Bookworm’s remarks.

‘Not true,’ said the Bookworm, whipping out a pair of silver spectacles. ‘You will be surprised to know that most people master the art of sleepwalking very early in life. Now, these are Observation Glasses. Put them on.’

‘I can see quite well, thank you,’ said Wisha, a little offended.

‘Can you?’ said the Bookworm. ‘Then why don’t you have enough in your Imagination to fill up this balloon?’

Wisha decided not to answer that question. ‘What’s going to happen when I wear these?’ she asked impatiently.

‘What’s going to happen?’ said the Bookworm, repeating her question. ‘What’s going to happen, Wisha Wozzariter, is that you’ll find things you’ve seen and not noticed. Things you’ve heard but not listened to. Touched but not felt. Said but not meant. Smelt but not experienced. Take all those things, my dear Wisha, and blow them into your balloon. Just do it! I’ll be back.’

What Wisha Saw

When she was all alone in the darkness again, Wisha put on her spectacles. It took a few moments for her senses to adjust to the feeling that everything around her was magnified. She could see the darkness of the room she was standing in; yes, actually see the darkness and its thick velvetiness.

All sorts of sounds came to her ears from beyond the room, each sound with its own texture: the rough, ringing sound of a squirrel’s tail against the bark of a tree; the whisper of leaves rustling on the almond tree outside her home; the thwack of a cricket bat connecting with a ball as the boys played their evening matches; the deep-throated rumble of monsoon clouds gearing up to shed their rain.

Other sounds, too, more frightening ones. The shrillness of brakes screaming for mercy before her neighbour’s car dashed into a tree last year; of the sparrows crying after the crow stole their eggs, and so on.

Wisha drew a sharp inward breath. With it came the smell, clean like soap, of the earth after the rain—and that feeling of running in and out of the rain, just in time, to the smell of dinner cooking.

Her fingers were tingling now, as if all ten of them were recalling their own memories: of the windowpanes quivering like piano wires against the wind; the stickiness of a torn flower petal; the furry nothingness of a butterfly’s wing; the rough promise of a page she had never read before.

There was a sigh building up inside her now, and that sigh was turning into a song, and that song was turning into a cry; and now she was crying, big tears rolling down her face, smearing their wetness upon her cheeks and dropping down uncertainly around her mouth.

Hands trembling, Wisha Wozzariter brought the balloon to her lips and she blew; she blew her entire being into that balloon. Everything she had seen but not noticed; heard but not listened to; touched but not felt; meant but not said; smelt but not experienced went rushing into that balloon. It grew larger—and larger—and larger—till it was almost bursting open from the life inside it.

When the Bookworm popped his head in, he found Wisha floating in her Solitude Room, light as a feather, astride a big red balloon.

Hero Zero

‘How do I explain what happened to me in that room?’ asked Wisha of the Bookworm.

‘I felt . . . I felt . . .’

‘Inspired!’ completed the Bookworm. He was curled up around a clear-blue bottle. A few round drops of something gold and glistening clung to the inside of it.

‘That’s your Inspiration, Wisha Wozzariter,’ said the Bookworm. ‘You were inspired in that room and when you’re inspired enough to write your book, this bottle will be full. So full that you’ll be able to spare a half-bottle for that auctioneer, you’ll see.’

Having said that, the Bookworm slid off the bottle and into Page 101 of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Wisha picked up her pen and as if she had always known what to do next, dipped it into the bottle of Inspiration and started writing.

But hardly had she written a line or two when she realized that she had imagined everything except a hero. Roald Dahl had Charlie, Lewis Carroll had Alice; Wisha Wozzariter had given her readers no one to love or hate.

‘Where’s Bookworm when I need him?’ she said, flipping through the pages of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. There was no sight of him. Wisha searched for another hour but the Bookworm did not return. She sat back, tired, and stared at the Inspiration bottle, at her Imagination Balloon, at the white door with its walnut knob leading to the Solitude Room—and thought of a way out.

Or a way in? Yes, that was it, thought Wisha, as she reached for the door to Solitude and opened it again. She stepped in and allowed the darkness to settle like fine dust around her shoulders. In the silence, she heard the whistle of a train coming in. This time, it was on schedule.

‘Stand aside for the Thought Express,’ whispered a voice in the darkness. ‘Next stop, Bargain Bazaar. Get on—or keep waiting. What will it be?’

Wisha couldn’t decide. Her stomach was knotting up inside her. This time, there was no Bookworm for company; she was all on her own. She felt the wheels

of the train start to move again. There was no time for second thoughts.

‘I’m coming!’ she cried, jumping on. As her thoughts hurtled her on to who knows where, her hands closed around something. It was a discount ticket of some sort. It said:

Dear First Time Writer

This ticket entitles you to 50% off at the Thrift Shop, the one-stop shop for Cheap Characters and Second-Hand Heroes.

The Superhero Salon

The Thought Express took Wisha to the Bargain Bazaar—well, almost. Most of the passengers wanted to get off at the Superhero Salon so that’s where the train stopped.

‘Sorry about that,’ whispered a voice into Wisha’s ear. ‘If you don’t get what you’re looking for here, the Bargain Bazaar isn’t too far off.’

Wisha alighted from the train, dazzled. The floor beneath her feet was paved with coins. All around her, white marble pillars rose up to a stained-glass roof, gleaming. Gold elevators swished up and down between the pillars as soft music streamed into the sunlit building. Fountains of silver water sprang up into the air.

‘May I help you?’ said a lady, dressed immaculately in black. Her smile seemed to rip apart her face.

‘I’m a little lost,’ said Wisha. ‘Where am I?’

The lady’s smile flickered like the flame of a dying candle, her lips thinning. ‘We-ell, if you don’t know where you are, perhaps you shouldn’t be here, hmmm?’

‘I came in on the Thought Express,’ said Wisha by way of explanation.

‘I’ll have a word with that engine driver later,’ said the lady, not looking pleased. ‘We can’t have anyone and everyone turning up here just because the Thought took hold of them.’

‘Please,’ said Wisha. ‘I’m here to find a Hero. I can pay.’

‘Suit yourself, take a look around then,’ said the lady, and she was gone.

There was nothing but the cash desks on the ground floor, so Wisha took the elevator up. ‘Floor One—Apparel,’ said the pretty elevator-girl, bowing. ‘This is where the heroes get their outfits,’ she said. ‘Unless you prefer to check out Floor Two first, that’ll give you an idea how they look once they have their hair and make-up done.’

‘No, thanks,’ said Wisha, bewildered. ‘I’ll just get off here.’

No one spared a glance her way as she walked around Floor One. All the sales staff was busy pandering to rich customers.

‘I’d like my hero dapper like James Bond,’ said a white-haired woman who looked like a schoolteacher. ‘No, not that suit, the other one.’

‘I want mine nice and naughty—like Artemis Fowl,’ giggled her friend, thin as a reed and tall. The hero standing before her looked too nice to be naughty. His face fell as the sales staff led him away.

A loud wail went up from the little girl at the other end of the floor. ‘Mommeee, she’s not pwetty enuff!’ she said, stamping her foot upon the ground. ‘I want a real fairy, a real fairy!’

‘Darling,’ said the little girl’s mother. ‘She is a real fairy. We’ll give her golden hair and some sparkly make-up and she’ll look better than a real one.’

The little girl was inconsolable and started howling in the most hideous fashion. The mother took her by the hand and tucked the fairy under one arm.

‘Take us to the Make-Up Section,’ she said imperiously to the saleslady. The fairy didn’t look too happy being carried away like that. Her wand fell on the floor as they left, but they didn’t stop to pick it up.

‘Uh, excuse me,’ said Wisha, stopping a sales clerk. ‘I’d like a hero, too.’

‘What would you like, madam?’ said the clerk, his smile reminding Wisha of the lady she had met on the Ground Floor.

‘I’d like a girl-hero,’ said Wisha. ‘She must be brave and strong and feisty.’

She quickly added, ‘Oh, and awfully clever, too!’

‘You’re asking for a lot,’ said the sales clerk. ‘It’ll cost you.’

‘I can pay,’ said Wisha proudly. Hadn’t she bought the Imagination Balloon for half a bottle of Inspiration?

‘Hey, Marcy, get a load of this,’ said the sales clerk, calling across the room to his colleague. ‘She says she can pay.’

Hoots of laughter emanated from the general direction of Marcy, wherever she was. Wisha squirmed in discomfort.

‘What’s so funny?’ she asked the clerk.

‘Ma’am, we don’t accept payment here. Only Frequent Shopper’s Cards. Do you have one?’

Wisha shook her head. ‘How can I get one?’ she asked him.

He tittered. ‘By shopping here frequently, of course.’

‘But I can’t shop here without a card, can I?’ asked Wisha, puzzled.

‘Of course you can’t,’ said the clerk. He was enjoying this.

‘This doesn’t make sense,’ protested Wisha. ‘You won’t let me shop here because I don’t have a card! But I don’t have a card because you won’t let me shop here!’

‘Now, ma’am,’ said the clerk, dropping his voice so low it was almost inaudible. ‘Let’s not create a scene. Why don’t we resolve this outside?’

It was a question, but the clerk didn’t wait for Wisha’s reply. He scooped her up by her waist and tucked her under his arm like bothersome baggage, then marched her past the elevator, down the winding stairs, and out the door of the Superhero Salon.

‘You’re out of your league here,’ he hissed as he put her down hard. ‘Try the Bargain Bazaar.’

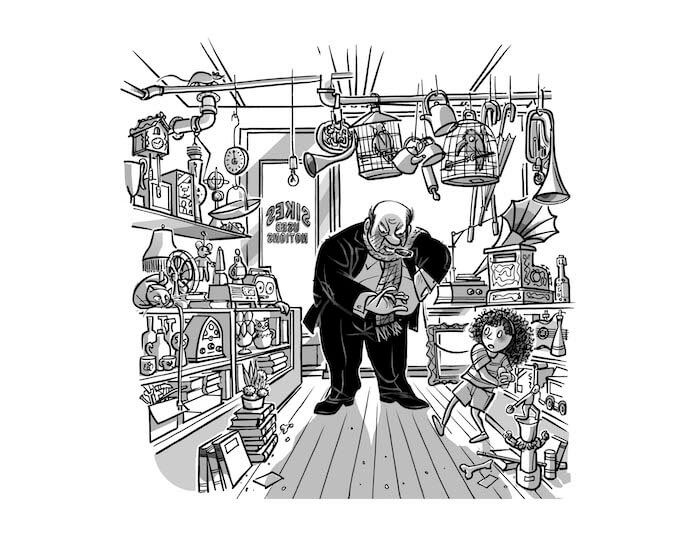

The Bargain Bazaar

The smooth pavement outside the Superhero Salon quickly gave way to a dirt-road pockmarked with potholes. Trails of slush marked the path to the Bargain Bazaar. Rusted poles propped up the tattered tarpaulin roof, and they were dripping with grease. The grey roof sagged at the corners, and through a large tear in the middle, you could see the sky, also grey.

Wisha coughed as a cloud of dust materialized in front of her. A stoutly built fellow in a black velveteen coat was dusting the shelves of his shop with a cloth that looked too dirty to clean anything.

‘Want a look at our second-hand wares, miss?’ he rasped, his voice sounding like he had stones in his throat.

Before Wisha could show any interest, he rattled on. ‘They’re a little worse for wear, our heroes, but that’s only because they’ve been used before.’

His eyes glinted like a knife-edge catching the light. ‘And we charge a little more for heroes that well- known writers once used. Dickens’ heroes turned up the other day, a little roughed up, but we’re getting them in order, as we speak.’

He clapped his hands twice. ‘We’ve got a customer here!’

‘No, you don’t,’ said Wisha. ‘I’d like to look around the bazaar, if you don’t mind.’

The man stepped in front of her. Up close, he towered over her. ‘What’s to look at, little girl? You think you’ll get better elsewhere?’

Wisha tried to move past him. ‘No, no, nothing like that,’ she hastened to say. ‘It’s just that I have this coupon for the Thrift Shop and I’d like to go there first.’

The man clutched at her T-shirt. ‘The Thrift Shop? Did you say the Thrift Shop? It burned down ten years ago. Give me that!’

His hand shot out, trying to snatch the coupon from her. Wisha screamed at the sudden shock of it all. He had his hands on the coupon now and he was tugging at it. She felt it beginning to rip apart. In horror, both she and the man let go of it.

A rogue wind whistled through the bazaar, whipping the coupon up and sending it fluttering across. Wisha stared after it in dismay, then pushed past the man and raced behind it. By the time she caught up with it, she was at the end of the bazaar, panting for breath. The ticket fell to the ground, as if exhausted. There was a nasty tear running through it, but it was still in one piece. Wisha stooped down to pick it up, but another pair of hands beat her to it.

‘You’ll want to show this to me,’ said a cheerful voice. A short fellow on tiny legs, sweating profusely, stood in front of her, waving the ticket in her face.

‘The Thrift Shop might be gone, but I’m the owner Mr Frugal and I’m still here,’ he said.

Wisha lunged for the ticket, but he stopped her. ‘You’re not the first person who seems to want this ticket. Give it back,’ she said. She couldn’t help staring at Mr Frugal, drenched in his own perspiration.

‘Ah, so I see that you’ve met Sikes, have you?’ said Mr Frugal. ‘He would do anything for that ticket, Miss Wozzariter, and if I were you, I’d guard it closely.’

Seeing her start at the mention of her name, he said, ‘Yes, of course, I’ve been expecting you. You don’t think you got this ticket just by Chance, do you? Never ever underestimate the play of Destiny in a writer’s fortunes.’

‘So I was meant to come here,’ said Wisha slowly. ‘You must have a hero for me then.’

‘I do,’ said Mr Frugal. ‘I had her somewhere,’ he said, looking all about him. ‘Now where is she?’

He took off his shoe and shook it out. A grey mouse fell out. A grey mouse that was rapidly turning purple. Purple!

‘Here she is!’ said Mr Frugal.

‘A mouse?’ cried Wisha in disbelief. ‘A mouse! And why did she just turn purple before my eyes?’

‘Er, this mouse has a rather strange—or shall we say special—quality . . .’ said Mr Frugal, looking a little embarrassed.

Wisha said nothing. In her mind, she was trying to come to terms with the idea of a hero many sizes smaller than she had imagined her to be, and of the wrong colour.

‘She turns purple when she’s . . .’ and here, Mr Frugal paused to clear his throat. It was easy to see that he was uncomfortable about this.

‘. . . scared,’ he said finally. ‘She turns purple when she’s scared.’

The mouse was hiding under Mr Frugal’s collar,

trembling with fright. At these last words from Mr Frugal, she jumped.

Mr Frugal dropped his voice to a whisper. Leaning in close, he told Wisha, ‘She’s even scared of being scared.’

‘Is this what you call a hero?’ cried Wisha.

‘Well, I don’t have to call her a hero,’ replied Mr Frugal. ‘You do.’

He smiled and added: ‘If you want to, that is.’

Then laughing a deep-throated laugh at Wisha’s dismay, he continued: ‘Still, it doesn’t get better these days, you know. Even heroes aren’t what they used to be. You’ll just have to make the most of her.’

Gently, he picked the mouse off his shoulder and handed her to Wisha.

‘She’s a good one,’ said Mr Frugal. ‘And she’s all I have left. You can take her for free; I have no place to keep her.’

The purple mouse twitched her whiskers as Wisha peered at her. Then she scampered

up Wisha’s leg and into the folds of her shorts. She sat there, quivering. It would take a lot of work to make a hero out of her, thought Wisha.

‘I guess I should be thankful, Mr Frugal,’ she said finally. ‘I’d better go.’

She walked away, back through the Bargain Bazaar and up the slushy streets.

‘Miss Wozzariter, wait up!’ shouted Mr Frugal, running up behind her. ‘I’ll walk you to the station. You won’t be able to catch the Thought Express from the Superhero Salon any more.’

Mr Frugal waited with Wisha and her purple mouse till the train came in. And when it did, he thrust the torn discount ticket back into her hand. ‘You forgot your ticket, Miss Wozzariter,’ he shouted as the train pulled out of the station. ‘Don’t let it out of your sight again. There’s a Golden Scratch Card behind it, you see!’

Wisha turned the ticket over and stared at the rectangular patch of gold on the back. ‘It’s for Luck!’ she heard Mr Frugal saying, his voice sounding so much farther away now. ‘A writer can be the best writer in the world, but without a stroke of Luck, he’ll go nowhere.’